CONCRETE HONEY

2011 Collaboration with Geoff Manaugh | Text by Geoff, Images by John Becker

ANIMAL PRINTHEADS

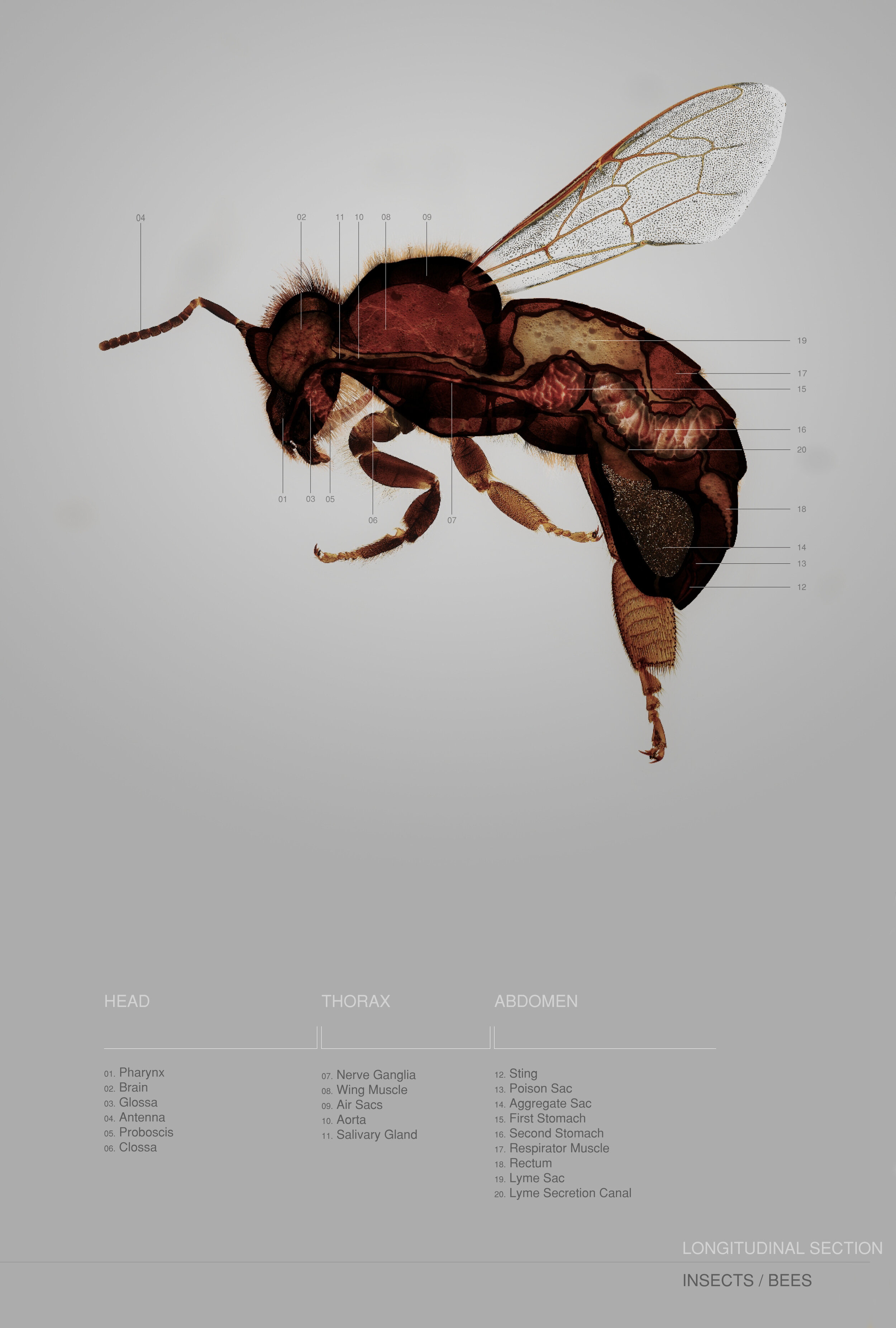

Spiders, silkworms, and honeybees, among other species, are organic examples of depositional manufacturing—they are sentient printheads, we might say, or living 3D printers. Creatures such as these have been domesticated throughout human history for specific creative ends, and, in many cases, their biological products have been deliberately farmed and manipulated.

Today, however, bioengineering is making the idea that animal bodies could be using as 3D printers more than just a poetic metaphor.

Whether it is to produce something as mundane as honey or silk, or to fabricate something far more outlandish, including automotive plastics, military armaments, and even concrete, the range of possible biological outputs from these species is on the verge of an astonishing transformation.

BEE PLASTIC

For the past half-decade, materials scientist Debbie Chachra at New England’s Olin College of Engineering has been researching what’s known as “bee plastic”: a cellophane-like biopolymer naturally produced by Colletes inaequalis, a bee species native to New England.

This weather-resistant yet biodegradable bee plastic could perhaps someday be used as an oil-free, organic alternative to the industrial plastics we use today, Chachra speculates, manufacturing everything from office supplies to car bumpers. The implications of her work—that domesticated cousins of these plastic-producing bees could effectively 3D-print whole car bodies, kitchen counters, architectural parts, and other everyday products, free from fossil fuels—is both extraordinary and environmentally promising.

However, the temptation to discover what might be possible through the genetic augmentation of these creatures opens a tantalizing but morally troubling zone of material speculation.

WOVEN BY GOATS

Recall, for example, that the U.S Army, in collaboration with Nexia Biotechnologies, was successful in its attempt to genetically engineer a goat that could produce spider-silk proteins in its milk.

The ultimate goal of producing these “Biosteel goats,” as they were eventually known, was to generate an unbreakable super-fiber that could be used in future battle gear; however, others have speculated that entire bridges, space frames, and other pieces of urban infrastructure could, surreally, someday be woven by goats.

The clear implication of this is that unprecedented new architectural forms and other design possibilities will emerge from collaborations with the bodies of genetically modified animals—but our ethics and regulations desperately need to keep pace.

CONCRETE HONEY

In 2011, inspired by these and other examples, designer John Becker and I set out to explore a series of science-fictional scenarios wherein bees have been genetically modified to produce a weather-resistant structural adhesive, similar to concrete, rather than honey.

In this scenario, a new urban bee species called Apis caementicium—or cement bees—has been deployed as a low-cost biological tool for repairing statues and architectural ornament, even producing whole, free-standing structures such as cathedrals.

Similar to molds used in casting concrete, the bees would be given a three-dimensional frame inside of which to perform their guided depositional manufacturing—that is, the augmented 3D-printing of new architectural and sculptural forms. This could include, for example, the iconic stone lions found outside the New York Public Library: damaged by exposure and human contact, those sculptures could be repaired by a family of concrete-printing bees working within a precisely affixed exterior mold.

FERAL PRINTERS

Our resulting illustrated narrative explores the ethical implications of genetic modification, the ecological consequences of engineered species escaping into the wild, and the architectural possibilities of animal collaborations such as these.

This is not a design proposal, however, but an inter-disciplinary narrative scenario developed for its aesthetic potential and, in many cases, its deeply problematic ethical repercussions.

In the end, what does it means to work humanely with biological design tools? Is genetic collaboration with other species such as this even possible without becoming a form of industrial exploitation? And, should we someday solve this moral quandary, what other-worldly new architectural possibilities might arise?